|

Kawasaki 250 Ninja

Major

service Major

service

When it comes to road bikes, there are many questions, but

only one answer: The 250 Ninja.

The Zimmerframe Stable has plenty of bikes, from vintage

German twins to modern triples and fours. There are race bikes and sport bikes

and naked hooligan bikes and touring bikes. Some are fast. Some are practical.

But if we could only keep one, it would probably be the humble little Ninja.

In production since 1986 and only given a major facelift

more than two decades later, in 2008, Kawasaki got it dead right with

the Ninja. It isn't the fastest or the absolute most comfortable over long distances, and

it doesn't have the luggage capacity of a big tourer, but it will do the ton, you

can ride it all day and its design is such that you can throw soft bags over the

seat and have plenty of room to pack for a long trip. Its light weight and low

seat make it a great beginner bike, but it also handles well enough that

experienced riders can have a blast on it. The little quarter-litre engine is

rated at 37.4 hp. That's nearly 150 hp per litre. Let that sink in a minute.

Miss Gill

got her Ninja as a learner bike, but with years of riding experience now she refuses to let it go. It has done everything from road trip to track

days. Yes, track! It isn't going to be the fastest thing out there, but ridden

well, it can embarass superior machines. Just ask the guy on the Ducati 1098 it

passed at Barber, or the Daytona 675 rider. Because it's not heavy or

intimidating, new riders - on the street or track - can learn quicker, building

skills rather than relying on horsepower to go fast.

to go fast.

The

Ninja is also fairly simple to work on. While it is a dual-cam,

four-valve-per-cylinder engine, it is very intelligently designed. It even comes

with a centerstand, which make routine stuff like chain lubrication infinitely

simpler. Gill does most of her own maintenance and she's very good at it. Other

than changing the oil and tyres though, we had done very little to the Ninja

since she bought it. At 12,000 miles, including many hours of track time, it was

due for a major service. The process was straightforward. The

Ninja is also fairly simple to work on. While it is a dual-cam,

four-valve-per-cylinder engine, it is very intelligently designed. It even comes

with a centerstand, which make routine stuff like chain lubrication infinitely

simpler. Gill does most of her own maintenance and she's very good at it. Other

than changing the oil and tyres though, we had done very little to the Ninja

since she bought it. At 12,000 miles, including many hours of track time, it was

due for a major service. The process was straightforward.

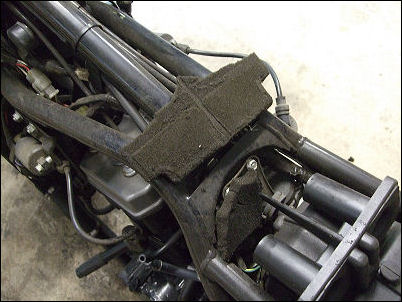

Remove all of the bodywork and you're left with a simple

engine in a simple steel tube frame. Again, it's a very smart design, as the

fairing, tank, seat and lower cowl come off easily so you can get to the

mechanical bits.

In addition to the seat, only five pieces need to come off and

you're ready to work.

Everything was fairly normal -- replace the plugs, change

the oil and filter, etc. The biggest revelation was the air filter. It's a

replaceable foam piece. This one had obviously never been replaced, as it

crumbled when we tried to remove it. I had to take the shop vac to it to get the

little pieces out of the airbox.

Removal of the valve cover is straightforward - undo the

bolts. There's plenty of room to slide it out, unlike some bikes. It does

require a little fiddling to get it past the coolant hose and over the cam

chain, but as these things go... simple.

You could go to a lot of trouble finding top dead center,

but really... just measure the clearance one pair of valves at a time. It's

easy: Once the cover is off, with the engine in gear, use the

rear tyre to rotate the crank until the pointy end of a pair of cam lobes is

facing directly away from the rocker arm. In the picture below, that's one of

the intake cam lobes pointed away from its rocker arm. The other lobe is on the

other side of the cam cap. Measure them as a pair by sliding a feeler gauge

blade between the cam lobe and rocker arm.

In the next picture, you can see how the cams operate the

rockers. These one on the left is about to close, while the one on the right is

about to open. When the rounded part of the cam is facing the arm (and the pointy end

is up), the valve is closed and there is a tiny bit of space - .08-.13 mm for the intake side, .11-.15

for the exhaust (since the exhaust side is hotter, the metal expands more and

needs more clearance).

Measure by sliding a feeler gauge blade between the cam

lobe and the rocker. It should just barely drag. If you have a set of metric

gauges, good for you. I use one that has increments of thousandths of an inch.

For instance, the .005 in. blade is .127 mm. Close enough for the .13 mm maximum

clearance.

Go for a clearance on the large end of the tolerance

scale, as the gap will close over time. If the right-sized blade fits with just

a minimal amount of drag, you don't need to adjust anything. Move on to the next

pair.

If the blade won't fit, or slides right in without

touching both surfaces, you will need to fix the clearance.

Now the cool part: Adjustment on the first-generation 250

Ninja is by screw and locknut.

There are no shims to replace, no need to remove the cams, and NO MATH to be

performed. You loosen the locknut and turn the adjuster with a screwdriver until

you achieve the desired clearance - you can actually adjust it until it just

barely causes friction with the feeler gauge.

Than hold the screw still and tighten

the locknut back down. Double check, because sometimes tightening the locknut

moves the adjuster screw just enough to change the clearance. You'll develop a

feel for it after you do the first couple. It's also a good idea to rotate the enging a few times and check again.

Some people accomplish the adjustment by holding a socket

with a pair of pliers or vise grips, and inserting a screwdriver through the

hole to work the adjuster. If you're only going to do this once, have

infinite patience and do not mind working in the insanely tight spaces of the

250 engine, go for it. However, while I'm all for improvising, the task is

made much easier with the "Kawasaki Special Tool," which costs about

as much as 15 minutes of shop labour.

It's basically a socket

welded on a tube with a handle on it, and a screwdriver that fits through the

tube. Slide it over the locknut, loosen nut, adjust screw, tighten nut, remove

tool. Easy.

One word of caution. DO NOT drop a feeler gauge down into

the bowels of the engine. See this?

It's the cam chain. It runs in a "tunnel" that goes all

the way to the bottom of the engine case and will swallow your feeler blade

whole. This would be a Very Bad Situation and can only be remedied one of two

ways: disassembly of the entire engine or profuse, heartfelt prayers to the

motorcycling gods combined wiht the skillful and/or lucky manipulation of the

magnet-on-a-stick that every toolbox should have in it. Ask me how I know.

I highly recommend removing the most-often-used blades

from your feeler gauge set and stringing them together on a very long loop of

string. This will let you use a blade to measure clearance without the rest of

the set getting in the way, and if you drop a blade (of course you won't, but

hypothetically, you know), it is easily retrieved since it's on a string.

If you're one of the unfortunate souls who bought a 2008

or newer 250 (or now 300) Ninja, either because you don't like the '80s-tastic

styling or because you just want something new, congratulations! Your bike looks

really cool, and might even be mistaken for a bigger, scarier Ninja instead of a

relic of the WHAM! era. However, your engine makes slightly less horsepower and

valve adjustment is by shims and buckets. I would suggest getting an older ninja

to correct the problem, but that may not be practical so go

HERE.

Otherwise, put everything back together and have a beer

while your friend with the newer Ninja is busy doing maths and worrying about

whether he's got the cam back in correctly.

Return home

|