|

2000 Kawasaki

ZRX1100

Resurrection from non-running to cool retro

ride, part 1

|

GPz550

|

My very first motorcycle was a Kawasaki GPz550 like the

one on the right. That was

back in the last century, when there was no such thing as a Motorcycle Safety

Foundation riding course. Humans were hardier then, if less sensible. You bought

a bike and you fell down a lot until you learned to ride it. I totaled mine,

twice, and after the second time I did what any sensible 20-something would do:

bought a bike with twice the displacement, the GPz1100.

That bike was stolen one night while I slept, probably by

someone looking to break it up for parts. The 1000/1100 Kawasaki engine was and

still is a popular basis for drag bikes. After that it was on to a long affair

with a 1975 BMW R90/6, but as they say, you never forget your first.

|

GPz1100 |

These days, it's really hard to find any GPz in decent

shape unless you want to shell out a lot of money. Most were modified (my 550

sported a 4-into-1 and K&N pod filters), ridden hard, and crashed.

Fortunately, Kawasaki captured the spirit of those early GPzs and their

Eddie Lawson Replicas when they brought out the ZRX1100 in 1997. As Sport Rider

magazine said in its review: "Anyone who followed AMA Superbike racing in the early '80s will know what this bike is all about. There's no mistaking the lime-green paint with blue and white stripes, the swoopy tail section, the piggyback shocks and the bikini fairing. It oozes nostalgia."

I finally got a ZRX of my own, but it hasn't been an easy

time.

Fresh off the van, it looked good. Relatively clean for

just under 30,000 miles, still with the original owner's manual and toolkit.

There were a few cosmetic abominations. Someone had

painted the face of the front brake calipers red, with a brush, and put silly

looking green stripes on the sidecovers. It also has a D&D exhaust which is

beginning to rust, and the previous owner had fitted an oversized rear tyre. But

still, not bad.

Closer inspection revealed a leaky fork seal, which

is pretty common on bikes that have sat around a long time as the seals can get

hard with age.

No biggie. I planned to give it a good tune up. Fork seal

would just be one more thing. Except there was a bigger problem - it wouldn't

run! At first, it would start after much fiddling, and it would idle, but it was

rough and sounded wrong. Checking the headers, it turned out that only one pipe

was hot, meaning it was only running on one cylinder. After three or four times,

it quit starting altogether.

Something was missing - gas or fire. Since when it ran,

one cylinder fired, my first thought was bad coils. But I ran all or the

diagnostics in the manual and everything checked out okay, although I did learn

one valuable lesson - the resistance of the coils needs to be measured with the

spark plug boot OFF. The boot adds resistance, the reading will be out of spec,

and you will think the coils are bad and you need to buy new coils.

Unfortunately, I only learned this after buying coils. Now

I have spares. Finally, I used the old-fashioned method of grounding the

spark plugs to the engine and looking for spark - all four cylinders had it.

That meant it was a fuel issue.

There is a vibrant on-line community of ZRX owners with a

very active internet forum, www.zrxoa.org, so

I decided to consult with them to see if anyone could diagnose the issue. Since

it's the interwebs, this of course led to a pissing match, with several members

insisting it was the battery - ZRXs need a healthy battery otherwise they will

just turn over and not start. I had measured the battery six ways from Sunday

and it checked out good. They did not believe me.

I ended up corresponding with Pete Aaronson, one of the

members who has a business making ZRX parts and repairing the bikes:

Hyperformance.

His knowledge and assistance turned out to be invaluable.

We agreed that since I had no idea how long the bike had

sat, how old the fuel was - any of it - the best way to start would be to clean

and rebuild the carbs. I could have done it myself, but Pete charged a very

reasonable fee and since he has done enough to know how to put 'em together

blindfolded, I figured that it was easier to send him the carbs.

Just getting them off was an adventure. They sit in rubber

mounts between the engine and a two-piece airbox. One of the most diabolical

bits of motorcycle engineering ever devised, the housings surround the frame.

You have to loosen both to get enough room to wrestle the carbs out, and even

then there's only about a half-inch of wiggle-room.

The ZRX also uses a push-pull, two-cable throttle assembly

that has to be undone.

Someone had already had them off, as they were marked with

tape at the carbs to keep track of opening and closing cables.

With the carbs out, you can see the front half of the

airbox assembly there on the left.

With the carbs out, everything gets plugged up to keep

things from nesting inside.

And the carb assembly goes on the bench for inspection.

This is the side that goes to the engine.

And the side that goes to the airbox.

I took off a couple of the float bowls to see what they

looked like inside.

Here's the float.

And the bowl, full of dirt and with a crushed and leaking

o-ring gasket.

While the carbs were off getting cleaned, the fork seals got replaced. I don't

think the forks had ever been apart or had their oil changed. That black stuff?

It's supposed to be clear.

The seals were a straightforward job. I could post

instructions and pics, but really, just go watch

THIS GUY. The ZRX forks are similar and the

process is nearly the same, although I highly recommend getting the

"Kawasaki special tool" to hold the damping assembly while tightening the bolt

in the bottom. It's the black cylindrical thing between the forks in the pic

above. It makes life MUCH easier and it's still cheaper than 20 minutes

of shop labor. Also, if you're going to do more than one set of forks in your

life, go ahead and get a fork seal driver. The universal type is fine for most

bikes. It's also cheaper than 20 minutes of shop labor and easier than trying to

make do with a piece of PVC. Here's the top of the fork right after removing the

cap. Take pictures and keep everything in the order that it was removed!

Meanwhile back in carb-land, things got weird. The carbs

came back, the bike started right up and ran okay up to about 3/4 throttle, then

it stumbled. It worked great trolling around in town, but for a spirited ride,

it was a no-go.

As it came to me, the airbox had no snorkel and had two holes cut in it. Pete said to

block off the holes and put a snorkel on, basically returning it to stock. That

made it worse. It still ran great around town but wouldn't even hit 70mph without

choking. This wasn't Pete's fault. We both assumed the carbs were stock.

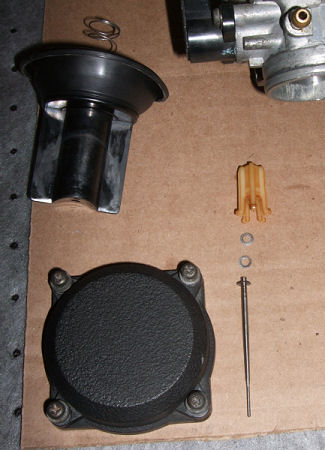

That assumption was wrong. The carbs came off again to see

what kind of jetting they had.

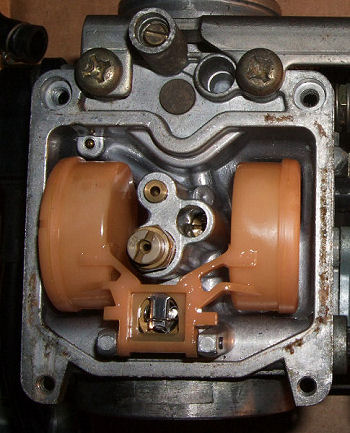

Here's the throttle slide assembly. Again, taking pictures

of everything helps keep track of how it goes back together.

This is the main jet.

Pete ID'd the jet. That little number identifies it as a Dynojet 132. The

needle also has an odd taper at the end and is a Dynojet item as well.

Turns out this bike was set up for a free-flowing air

intake and I'd been going the opposite direction, returning it to stock. Another

lesson learned - never assume anything is stock on a used bike.

This particular bike had a Dynojet "Stage 3" jetting kit,

which was actually a good thing. According to Dynojet's instructions, that size

jet should be used with pod-style filters, which I'd been thinking about using

anyway. Now I wouldn't have to buy a jet kit.

There are pros to going with pod filters (like more airflow and all

the fact that all the cool kids

use them) and cons (like more heat from the engine getting to your legs, and they can get soaked in the rain), but the

biggest factor in my decision was that I did NOT want to deal with that airbox

setup any longer, especially if I was going to have to take the carbs on and off

in the process of setting them up. When it takes longer to remove and install the carburetor

assembly than it does to tune them, something's wrong.

I set the needle height according to Dynojet's

instructions and put the thing back together, along with a set of K&N pod

filters, just like on my old GPz.

This also meant removing some emissions plumbing. For

instance, there is a breather apparatus connected from the top of the cam cover

to the airbox. No airbox meant this had to go. The picture below shows the tube

going into the top of the cover.

You can buy really cool billet blocking plates anywhere

from $20 to $50 a set. Being a member in good standing of the Poverty Riders

International, I opted for the two-cent solution.

I figured there would be more tuning - needle height, air

screws - but once back together, it ran like a champ and well over 70. How much

over? Ain't sayin'. But it's very, very good.

That red filter on the lower right is a breather filter,

$10 from Auto Zone. It caps off the end of the crankcase breather tube that used

to go to the airbox.

Now that it's running, all I have to do is either fit a

new exhaust or get this one ceramic-coated, service the brakes, check the

valves, and do all the other stuff I had planned in the first place. Stay tuned.

Return home

|